He stopped the hunger strike when the legislation failed to pass.

“Okay, that didn’t work. So really it’s how do we pick ourselves up and where do we go from here?” asked Nick Knudsen, executive director of DemCast USA, an advocacy group that uses digital media for voter mobilization.

Knudsen posed his question during an online town hall on Monday organized by the D.C.-based Transformative Justice Coalition. The question — “Where do we go from here?” — was also the theme of the town hall and the name of a book that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in 1967. In a speech that year, the civil rights leader said that to answer the question, you must first recognize where you are now.

Barbara Arnwine, founder of the coalition, recalled talking with other activists after the voting rights legislation died in Congress and being surprised that some were “as depressed and upset as they were about where we are.” It wasn’t as if losing this one vote was the end of the struggle, she said.

But it was dispiriting.

The details of what was behind the insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, are still being uncovered. But the purpose was clear.

“What exactly were the insurrectionists trying to overturn?” asked Cliff Albright, a co-founder of the group Black Voters Matter, during the town hall. “Votes. Not just in certain states but certain cities.”

He cited three with large Black populations: Philadelphia, Atlanta and Detroit. “It wasn’t just an attack against democracy, it was an attack against Black folks,” Albright said. “We have to be willing to call this out for what it is.”

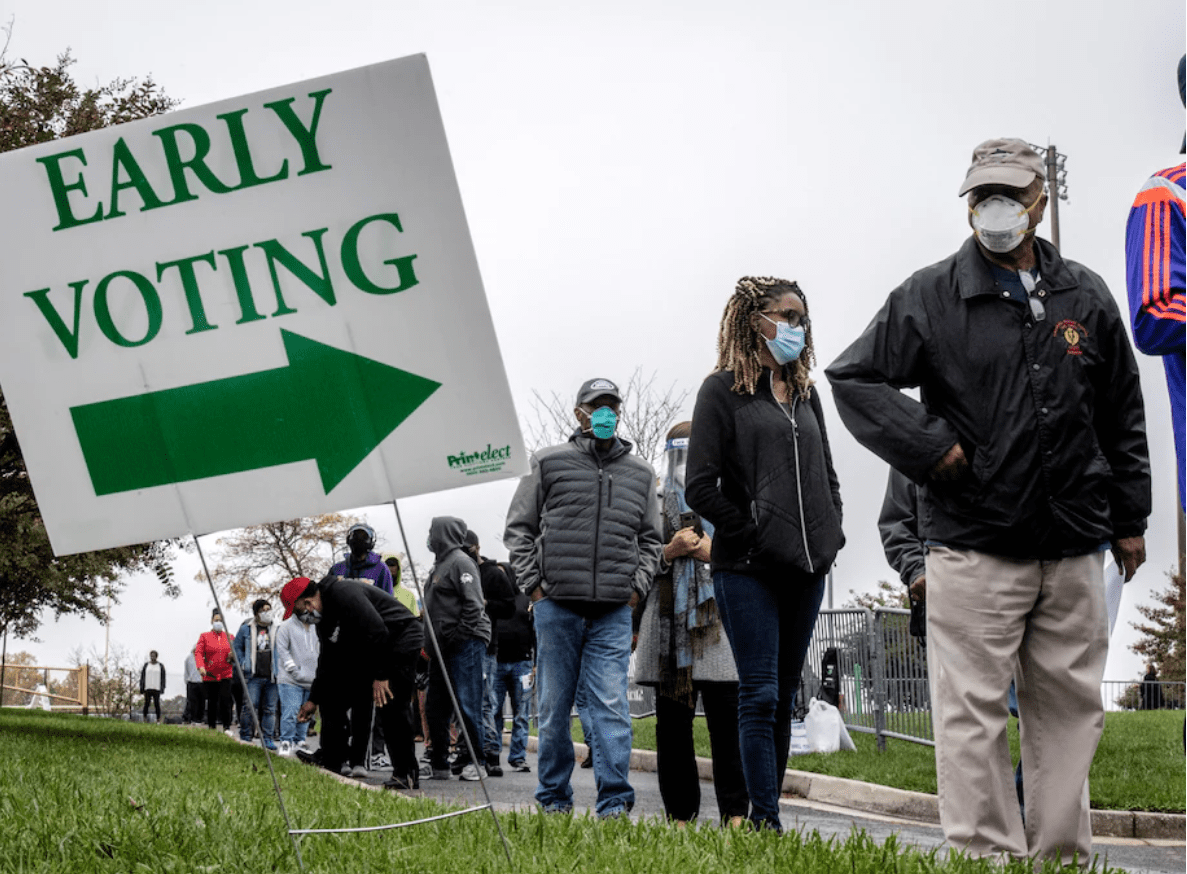

Last year, 19 states passed 34 laws that would restrict voting, according to the Brennan Center, and more than 440 bills that would restrict voting are pending in 49 states.

The restrictions, both passed and proposed, echo obstacles to voting that Black people faced during the post-Reconstruction and civil rights eras. Understanding the significance of those periods requires knowledge of America’s racial history. And attempts are being made to suppress that, too.

“There is a saying that those who don’t know their history are bound to repeat it,” Kim Crenshaw, a law professor at the University of California at Los Angeles, said during the town hall. “That is the point of attacking critical race theory — to take away our history so you can’t see the connection between suppression of our voting, suppression of our protest and suppression of our knowledge.”

Voting rights activist Helen Butler is part of a coalition fighting efforts to restrict voting access in rural Lincoln County, Ga., where she lives. She told those at the town hall how election officials have been attempting to reduce the number of polling places from seven to one. With only one polling place, some residents would have to travel up to 15 miles to vote, she said.

“It starts with the takeover of local boards of elections, then they go after voter registration and begin determining who gets to certify absentee ballots,” Butler said. Then, she said, the apparatus will be in place for the “takeover they were looking for during the insurrection.”

Knudsen urged activists to keep pressing the members of Congress to pass federal voting rights laws. “Don’t let them off the hook,” he said.

He said it was important for voting rights activists to think local, act local, act in their own communities. “Find organizations that are doing important work on voting rights and connect with them, and if you’re already connected, double down because there is a lot of work to do to,” Knudsen said. He also recommended that activists be prepared to document any problems people have exercising their right to vote: record and share incidents at polling places, collect the stories of people who have to wait in long lines or are asked to show unnecessary identification.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) recently proposed establishing a special police force to oversee state elections. A handpicked police force, reporting to the governor, could intimidate both elections officials and voters.

Many people at the town hall remained depressed. But they were also just as determined not to let Congress’s failure to act be the end of the story. Arnwine, referred to as the “election protection queen” by coalition chairman Daryl Jones, remained optimistic, energized and inspirational throughout.

“In 2020, we organized, we educated the people, we changed laws, state by state,” she said. “We will do it again, outshine and out-organize and make things happen that people said could never happen.”

Where do we go from here? The town hall had made the answer obvious: to vote.

Read more from Courtland Milloy