Warnock’s political career — and democracy in Georgia — could hinge on the most dangerous provision of the state’s new voter suppression law.

Late last month, Georgia Republicans began a process that could end with them seizing control of election administration in Fulton County — a Democratic stronghold that encompasses most of Atlanta.

Under Georgia’s new election law, SB 202, the GOP-controlled state elections board may remove a county’s top election officials and replace them with a temporary superintendent (although this process will likely take months as the board has to jump through a few procedural hoops first). Once such a superintendent is in place, they can disqualify voters, move polling places, and even potentially refuse to certify election results.

Voter suppression laws are nothing new, even in the post-Jim Crow era. And Georgia’s SB 202 is hardly the first effort by Republican state lawmakers to skew elections by making it harder for Democratic constituencies to cast a ballot.

But prior efforts to restrict the franchise frequently placed unnecessary hurdles in the way of voters, such as by requiring them to show certain forms of ID or by limiting where and when voters can cast their ballot. These sorts of laws are troubling, but they can be overcome by determined voters.

SB 202, by contrast, is part of a new generation of election laws that target the nuts and bolts of election administration, potentially allowing voters to be disenfranchised even if they follow the rules.

Because state voter suppression laws targeting ballot counting and election certification are relatively new, Democrats did not come into 2021 with a legislative proposal to address these laws. Democratic leaders’ primary voting rights bill, the For the People Act, includes a grab bag of provisions intended to neutralize state laws making it harder to vote. But the For the People Act’s drafters did not anticipate something like SB 202’s provisions allowing the Republican Party to take control of election administration in Democratic counties.

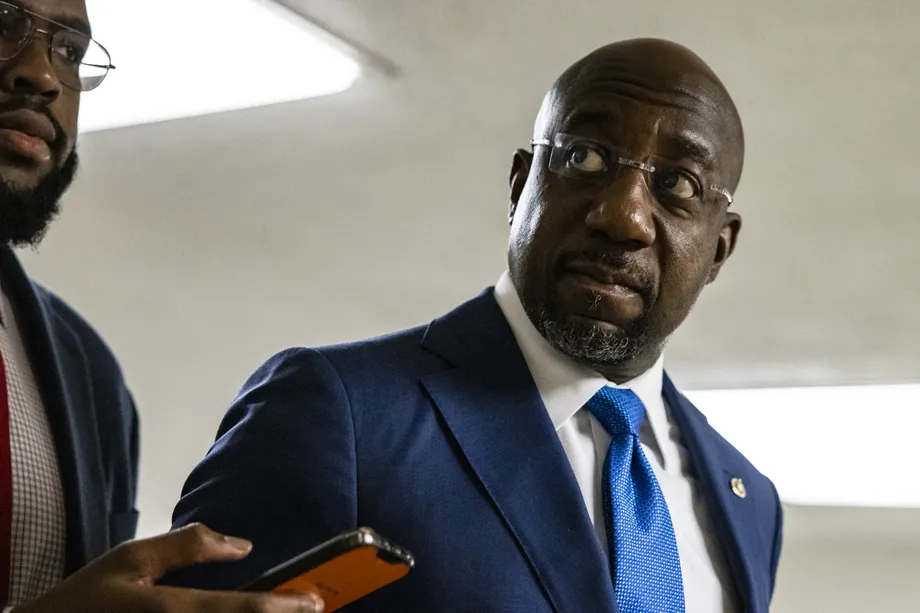

Which brings us to the Preventing Election Subversion Act of 2021, a bill introduced by Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) that seeks to fill that gap.

It doesn’t prevent Georgia’s elections board from removing a local election official, but it does impose some procedural safeguards intended to prevent local officials from being removed for partisan reasons. Among other things, it allows such officials to sue for reinstatement in federal court.

Additionally, the bill would make it a felony to harass or intimidate election workers in order to interfere with their official duties. GOP lawmakers in some states, including Texas, are pushing legislation making it harder for election workers to remove partisan observers who disrupt an election. Warnock’s bill would subject the worst-behaved election observers to criminal charges.

Realistically, Warnock’s bill has a long way to go before it becomes law. Warnock is reportedly in negotiations with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) to include safeguards against “election subversion” in a package of voting rights reforms that enjoys Manchin’s blessing. As the most conservative Democratic senator in an evenly divided Senate, Manchin is key to advancing any meaningful voting rights legislation.

And, even if Manchin signs on to the Preventing Election Subversion Act, that support is unlikely to amount to much unless Democratic senators unanimously agree to eliminate the GOP’s power to filibuster voting rights bills. Plus, there’s always a risk that an increasingly conservative judiciary will refuse to enforce new voting rights legislation.

But, at the very least, this bill is a sign that Democrats understand that the GOP recently escalated its tactics in the voting rights war, and that Democrats — and democracy — need an adequate countermeasure.

What exactly could the Preventing Election Subversion Act do in Georgia?

SB 202 presents a devilish problem for federal policymakers.

On its face, SB 202 creates a process that can be used to remove local elections officials who violate the law, or who demonstrate “nonfeasance, malfeasance, or gross negligence in the administration of the elections.” Few people would argue that election officials who repeatedly break the law, or who prove incapable of doing their jobs well, should remain in office. It’s entirely reasonable for a state to create a nonpartisan process to remove officials who are bad at their jobs.

The problem with SB 202, however, is that, in effect, it creates a partisan process to remove local elections officials. The bill ensures that Republicans will control four of the five seats on the state elections board for as long as the GOP controls both chambers of the state legislature. (As they have since 2005.) And it removes Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican who rebuffed former President Donald Trump’s attempts to toss out Joe Biden’s victory in Georgia’s 2020 election, as chair of the state board.

The Preventing Election Subversion Act includes several provisions that would diminish the GOP’s ability to take over local election administration in Georgia — and in other states that enact SB 202-style laws. One of its central provisions is that statewide officials may only remove a local elections official “for inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.”

Of course, SB 202, at least on its face, also gives similar protections to local elections officials. But SB 202 allows the GOP-controlled State Elections Board to determine if an official committed malfeasance. Warnock’s bill would allow a local elections official targeted by SB 202 to sue in federal court for reinstatement.

Thus, the ultimate determination of whether a local official performed their job so poorly that removal is warranted would be made by federal judges who, at least in theory, are less likely to be motivated by partisanship than a state board dominated by Republicans.

Warnock’s bill also includes provisions to ensure that such a federal lawsuit is vigorously litigated by a well-financed team of lawyers. Among other things, it provides that a local election administrator who is wrongfully relieved of duty may receive “reasonable attorney’s fees” if they file a successful lawsuit.

And under the bill, when a state begins proceedings to remove a local official, it must inform the US Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division that it has done so, and the Justice Department may also challenge the state’s effort to remove such an official in federal court.

The Preventing Election Subversion Act only works if federal judges are committed to the rule of law

The basic theory underlying the Preventing Election Subversion Act is that federal courts can be trusted to stop partisan efforts to seize control of local election administration. But it’s far from clear that this theory is correct.

The Supreme Court, with its 6-3 conservative majority, has generally been hostile toward voting rights statutes. In Shelby County v. Holder (2013) the Court struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act — the primary federal safeguard against racist voter suppression — based on an entirely novel reading of the Constitution that is at odds with the Constitution’s text. Similarly, in Brnovich v. DNC (2021), the Court imposed new limits on the Voting Rights Act that have no basis in that law’s text.

Congress, in other words, could pass a law that effectively neutralizes the most virulent provisions of SB 202, but there’s no guarantee that the Supreme Court will follow that law.

Another danger is that, should the Preventing Election Subversion Act become law, individual federal judges may apply that law in bad faith.

Imagine, for example, that Georgia Republicans uncover a few instances where Fulton County’s election board made suboptimal management calls — the sort of minor errors that are inevitable in any operation tasked with counting hundreds of thousands of ballots. Because Warnock’s bill allows local officials to be removed for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office,” a partisan federal judge might claim that these minor missteps justify removal.

And then there’s the risk that the Supreme Court — perhaps by engaging in the same sort of textually challenged legal interpretation that it performed in Shelby County and Brnovich — could strike down a federal law governing who may administer elections.

As a general rule, federal courts are reluctant to hear lawsuits challenging how a state allocates power among its “political subdivisions.” Though there are some exceptions to this general rule, typically, if Georgia decided to take over Atlanta’s police force, or its schools, or some other government agency that is typically led by local Atlanta officials, federal courts would not intervene.

The Supreme Court has also held that the federal government may not “commandeer” state officials and demand that they perform their jobs in certain ways. A conservative Supreme Court could potentially extend this doctrine to prevent the federal government from shaping who will administer elections in Fulton County.

But the Constitution also gives Congress an unusually broad power to regulate congressional elections. Although the Constitution permits states to determine “the times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives,” it also permits Congress to “at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators.”

So, as the Supreme Court held in Smiley v. Holm (1932), federal law may “provide a complete code for congressional elections,” regulating such granular matters as “notices, registration, supervision of voting, protection of voters, prevention of fraud and corrupt practices, counting of votes, duties of inspectors and canvassers, and making and publication of election returns.”

A Supreme Court that believes it is bound by the text of the Constitution, in other words, should uphold Congress’s ability to prevent Georgia Republicans from taking over the administration of congressional elections in Fulton County. But, of course, America is ruled by the same Supreme Court that gave us Shelby County and Brnovich, so there is no guarantee Warnock’s bill would be upheld, even if it becomes law.